The article below was provided by Angela Harutyunyan, an art curator originally from Armenia but now based in Egypt who attended the opening of the Biennale di Venezia (the Venice Art Biennial) earlier this month.

The Armenian Pavilion at the 54th International Art Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia (the Venice Art Biennial) entitled “Manuals: Subjects of a New Universality” conceptually deals with the relationship of the particular with the universal in the context of identity and offers various aesthetic solutions to the politics and economics of survival.

By overidentifying with the attributes of the dominant power, Grigor Khachatryan’s National Center for Planning Accidents (pictured, below) presents power as a theatrical act and a performance. In a designated room in the Armenian Mekhitarist Mourad Rafaelian College (also known as Palazzo Zenobio) Khachatryan has reproduced a room for official meetings with attributes such as a central carpet, a long table, soft office chairs, tall natural flowers placed along the length of the table as well as photographic documentation of previous official meetings. Even the attendant of the Pavilion automatically becomes Khachatryan’s secretary.

Mher Azatyan’s installation (pictured, below) delves into a formula for survival in verbal and visual fragments of the everyday. The ruins of soviet universality—photographic snapshots of abandoned and accidental objects and sites are uncomfortably crowded on the walls of the hallway connecting two larger rooms, as if the positioning of one photograph intervenes into the space of another. As opposed to this piling up of the visual fragments, Azatyan’s texts seem to breathe freely in a larger room where they appear and disappear according to the viewer’s movements in the room. Azatyan’s short samples of “minimalist poetry” are either collected from the vernacular language or “authored” by the artist. Even though most of them are authored, nevertheless, they are collectively produced utterances that structure everyday communication, or often the lack of it: “We burn wood, and another winter will pass,” “The bee produces honey. What does the artist produce?” and “Money doesn’t like equality.”

The narrative of the Manuals concludes with Astghik Melkonyan’s guidebook on daily survival or instructions on how to manage one’s monthly salary (pictured, below). The construction made of steel and Plexiglas carries various prescriptions useful especially for artists living in the socio-economic conditions of today’s Armenia. Both Melkonyan’s work and the Odyssey of its transportation to Venice epitomize the cultural politics in contemporary Armenia as well as raise fundamental issues related to the status of the artist as well as art’s symbolic and material value.

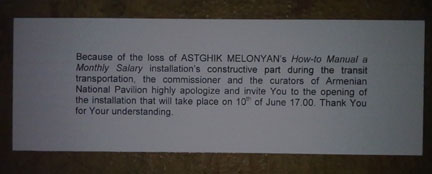

On Jun. 4, during the crowded opening of the Armenian Pavilion, the doors of the room reserved for Melkonyan’s installation were locked. A note was hanging with an inscription that due to the “loss” of the work during its transportation, a second opening was scheduled on Jun. 10. The reason for this failure was the fact that various elements of the construction were forgotten and left behind in Yerevan. What followed where haphazard, uncalculated and ultimately failed attempts to manufacture and construct the installation from aluminum, until a decision was made to open the Pavilion without Melkonyan’s work.

However, neither the curator’s neutralizing ascription of responsibility to a third person, nor the celebratory attitude of the organizers could conceal the fact that in case of the Armenian Pavilion it was not the artist who appeared in the center of the project — instead, it was the glitter of pure representation spiced up with a large audience, clinking wine glasses and even the presence of Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili who visited the Pavilion in a move of cultural diplomacy.

What lies between the curatorial team’s initial mission to use the Pavilion as an opportunity to locally intervene into the cultural politics and the project’s ultimate destiny as pure representation is a long and painful negotiation of power, establishment of professional positions vis-à-vis the Ministry of Culture and the commissioner and manifestations of these positions. The curatorial team consisting of Vardan Azatyan, Ruben Arevshatyan and Nazareth Karoyan experienced some “casualties” before Venice as Azatyan formally withdrew from the team three weeks before the opening of the Biennale.

According to Azatyan’s interview to Epress.am, the main reason for his withdrawal was the delay of financial resources that the commissioner was to secure. This created a situation when the failure of a single miniscule detail could result in the collapse of the entire project. However, behind Azatyan’s solely pragmatic decision stand serious professional considerations with ethical consequences which have ramifications for cultural politics. In a situation when a failure to oversee small details due to the lack of finances threatens the entire project, curators are forced to find situational and momentary solutions. This can create conditions in which not only their professional integrity is threatened as the production of the project is essentially out of their control, but also their working relationship with the artists and the responsibility towards the project. But most importantly, according to Azatyan, “as a result, the vicious work method common in Armenia was again employed — based on sacrifice… Instead of carrying out their direct duties, they [public institutions] act as symbolic bureaus, which in the name of the ‘homeland’, in the name of ‘the nation’s honor,’ are ‘authorized’ to exploit and decimate the country’s most expensive resource — human energy.”

Instead of becoming a catalyst to have an impact on local cultural politics in Armenia, the Pavilion (even if it is an engaging exhibition) turns into a space for pure representation where the curators (willingly or by default), organizers and those accompanying them project their phantasmagoria (related to power and recognition), where the contact with contemporary art becomes a matter of “lifestyle” and the artist turns into a tool to fuel these desires and associations. When art is measured according to how many tons it weighs, representation as an event becomes the guarantor of the project’s success, situationism turns into the only possible working method and the artist appears as merely a reason to secure the success of the event, then it is pointless to expect a curatorial position, reflection or responsibility. What might seem a simple failure to bring together one installation is a symptom of deeper processes and attitudes within the cultural politics in Armenia.

To expect responsibility from the Ministry of Culture or the commissioner is in vain since, according to Karoyan, they are “inexperienced” in the organization of the Pavilion or dealing with the contemporary art scene. But also, Arevshatyan’s and Karoyan’s decision at the time of Azatyan’s withdrawal to carry on with the project and “save” it, arguably, did not allow the official institutions and their actors to realize their share of responsibility and gain “experience.” In this situation, the whole responsibility by default lies with the curators whose most important task (apart from playing cultural politics with public institutions and their private appointees) is to closely engage with an artist’s practice and provide the best possible conditions for the production of the work and subsequently, the exhibition. This is possible only when the artist’s practice appears at the center of the project. Within our specific economy and distribution of resources, it is the curator’s task to enable the artist as much as possible to become the main economic subject as well as the subject of aesthetic decisions. The curator’s task is not so much the mediation and translation between the art work and its publics (only those works need “medical hermeneutics,” if we borrow Boris Groys’ term, that need to be “saved”). Neither is it the desire to slice a bigger pie of art’s symbolic economy, but to be attentive and serious about the most trivial of administrative, organizational and formal details — starting from the artist’s accommodation to the preparation of the press release.

Finally, it is the curator’s task to work with the artist, and not at the expense of the artist. It is only then we can celebrate the representational success of the Pavilion when the experience of its organization results in an impact in the local cultural policy. The participation in the world’s oldest and most prestigious Biennale certainly involves a branding operation and carries with it cultural capital that can translate into the local cultural politics. This involves a changed attitude towards the artist’s practice, a demand from public institutions to provide access to its resources for the producers of contemporary art and its discourses as well as active involvement in the dominant politics of representation.

When the artist’s experience with the Biennale ironically becomes identical to the content of her work (a manual of how-to-do with the per diem and accommodation and how to construct a laborious installation out of nothing) and turns into a strategy and tactic of survival, then we can easily conclude that the cultural politics of the Pavilion have failed, even if the representation of the event has succeeded.

All photos property of and provided by the artists.

Epress.am News from Armenia

Epress.am News from Armenia